This is a re-edited essay I wrote as part of my UCL Film Studies Masters’. Definitley one for the more ardent cinephiles- Metropolis and Triumph of the Will are required watching before reading!!

Metropolis (1927) and Triumph of the Will (1935) are two of early German cinema’s most extensive technical achievements which employed vast masses of people to produce unmatched visual spectacles. However, these similarities have also provided a base of critique which claims Fritz Lang’s 1927 masterpiece contained proto-fascist sentiment which was central in the development of Leni Riefenstahl’s infamous propaganda piece. The historic leader of this charge has been the famed, although recently more maligned, German cultural critic Siegfried Kracauer, who utilises his theory of The Mass Ornament to argue both films reduce the masses into dehumanised and decorative patterns which are then bent into endorsements of totalitarianism. The writer Stefan Johnsson has more recently and pointedly taken up this claim to call Metropolis ‘a dress rehearsal for fascism’ for how it presented the masses as in need of leadership.

There are certainly formal similarities between both films which render the individual part of a patterned whole. However, a closer probing uncovers nuanced and crucial differences in each filmmaker’s formation and manipulation of these geometric forms, which critically undermine the links drawn between them.

The Masses in Abstraction

Metropolis and Triumph both contort their masses into rigid structures, where individuals form mere fragments of larger shapes, and as Kracauer writes in doing so create an ornament ‘detached from its bearers’ as ‘an end in itself’. These ornaments offer visual pleasure for audiences through patterns, shapes and rhythms which lure in the eye and desensitize critical faculties. Triumph’s parades, rallies and congresses fill the screen with columns of thousands of men, often shot from crane-shots or aerial photography, transforming its meetings into grand spectacles which engross the audience. For example, its influential war memorial sequence, since copied in films like Star Wars, saw 97,000 SA members and 11,000 SS members shaped into rigid columns or form part of a rhythmic procession circling their outside. Similarly, the twilight rally made use of a parade of flags filmed from multiple angles in which their flag-bearers are indistinguishable from the flags which dominate the screen. Thus reducing them from individuals into simple architectural patterns. Indeed, throughout Triumph we see standards, torches, and even spades beinged transformed into decorative patterns which sit above and obfuscate their holders.

This mass aestheticization is also present in Metropolis for, as Luis Buñuel commented upon the film’s release, it’s workers “fill a decorative role…[with]…their beautifully choreographed and balanced movement”. This is seen throughout the film, including in the workers’ shift change where they and their subterranean city are formed into rectangular divisions, and its third act flood which contains one of the film’s most iconic images, in which children cling around the character of Maria in pyramidal and circular shapes. Just a few moments later we even get a shot reminiscent of Triumph’s flag-bearers in which a high angle shot shows Maria clearly lit while the children clinging to her in fear are shrouded in darkness.

Ideological Corruption vs Mechanical Fetishisation

However, such aesthetics serve very different purposes in each film. In Triumph they aim to depict Nazism as the pure embodiment of the masses and the nation by breaking the individual down into a a piece iconography which can sit alongside Nazi paraphernalia. The film’s opening congress for example begins with a low-angle shot of a Riechsadler (Nazi Eagle) watching over everyone, before cutting to a high-angle shot of an assembled rally framed with a series of Nazi banners in its foreground. This intimately links the rally’s abstracted members with Nazi imagery, transforming them not merely into ornaments but Nazi ornaments. This technique is used constantly by Riefensthal who is not just aestheticising but also politicising her crowds.

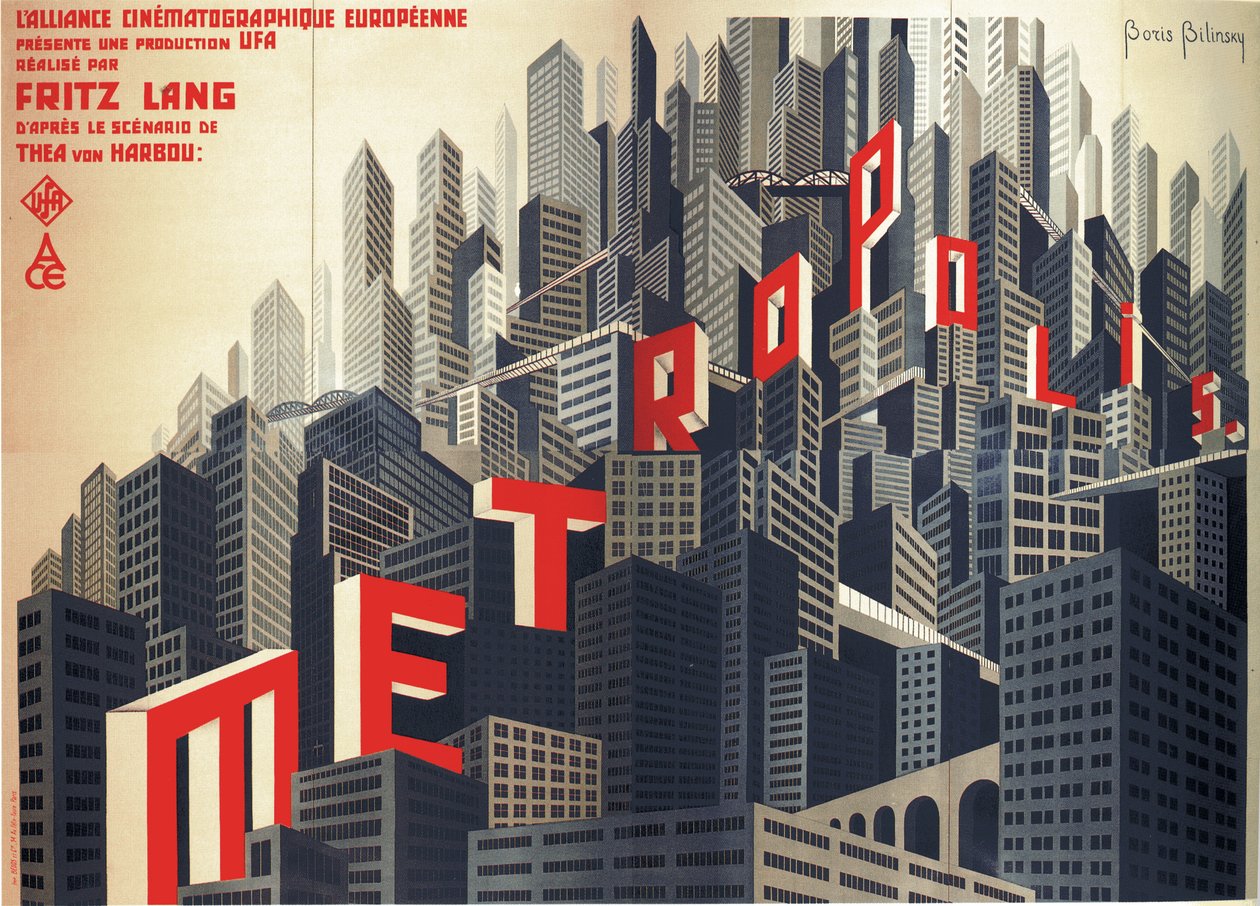

In contrast, Metropolis is driven by Lang’s fascination with the ‘Neue Sachlichkeit’ (New Objectivity) movement which was obsessed with the order and rigidity of technology and industrialisation. Lang fetishised the machine and emphasised its pleasurable display over all else. As a result, his abstracted masses are simply extensions to his fetishisation of Metropolis’ machines. This is shown in the film’s opening, which begins with intersecting lines that form the word ‘Metropolis’ before turning into the city’s majestic, structured skyline. Lang then takes us through the different levels powering Metropolis starting with dissolving images of its machinery, including pistons and spinning wheels, before cutting to an ornate whistle which signals the workers’ shift change into their rectangular blocks. This triumphalist sequence, the words Metropolis even glow, creates a continuum of geometric images from the city down to the worker and treats them as equal components in celebrating Metropolis’ technological majesty.

Thus, the workers are abstracted not for political reasons but merely to transform them into mechanical ornaments, Lang himself even called Metropolis a “picture in which human beings were nothing but part of a machine”. Indeed, the movements and shapes of Metropolis’ workers do reflect the rhythm of its machines, even when they are destroying them. During the collapse of the heart machine, it starts sparking and speeding up, and this visual excitement is cut with reverse shots of the equally excited and electrified masses. This once again integrates them into the mechanical world even during its demise.

The Insidious Nature of Organic Community

Further differences can be found in how each filmmaker positions the individual within the masses. Riefenstahl, for instance, establishes superficial bonds between her individuals, and depicts their willing sublimation to the abstract mass. Something which in turn presents it as the true expression of their individual wills. This is often done through individual close-ups, especially during reaction shots to Hitler’s speeches, which then cut to the crowds in their entirety and establish a strong link between the mass and the individual.

However, things are most inventively achieved during the labour service rally. This contains a sequence involving one man looking offscreen to his left and asking fellow workers where they are from, which is then followed by close-ups on different men answering the question while looking right. This makes use of the ‘180-degree rule’, and implies these disparate men are having a direct conversation establishing artificial bonds between them. This then continues with more men answering the question, but the film no longer cuts back to the original questioner and they all look off to the left with the entire rally chanting together ‘One Fuhrer, One Reich, One Germany’. Thus, Riefenstahl carefully constructs the labour masses with both a false sense of community and as consenting to their sublimation into a singular body. This was central in fascist propaganda as outlined by the influential philosopher Walter Benjmain whose theory on the ‘aestheticizing of political life’ stated that Nazism uses ‘corrupt compositions of the masses’ to ‘supplant [true] class consciousness’. This, he argued, gave false ‘expression to the masses’ without granting them actual rights or representation.

In contrast, Metropolis makes no concerted effort to present its abstract masses with a false sense of community or individuality. In fact, its workers are most expressive when taken out of such formations. This occurs in the catacombs when the workers are fewer and more organically scattered about, and being preached to about the industrial abuses they face. Metropolis’ robot-Maria asks them ‘Who is living fodder for the machines of Metropolis?’ and ‘Who smears the machine-joints with their own marrow?’ to which they respond “ME!”.

The Lone Superior Führer

Triumph also consciously constructs its crowds around one single authoritative figure, Hitler. This is achieved through match cuts between Hitler’s face and those in his rallies which establish him as a point of focus and prime authority. Riefenstahl’s use of low-angle camera pans in the film’s youth and twilight rallies also produces a similar effect, as they rotate slowly and deliberately around the Führer in a 180-degree sweep. This creates the impression that Hitler is being viewed from all sides as an unrelenting object of attention for Germany. The camera even appears embedded within the crowds as it includes the tips of flags within its frame. Crucially, Hitler is not only a figure of authority but also a figure of superiority. He is regularly filmed from low angles and against a backdrop of only the sky. This works to separate him from those around him and situate him on a different plain of being.

Thus, in Triumph the masses are constructed to not only be an end in itself but to pivot around Hitler as its commanding core. It functions as a physical manifestation of Triumph’s message to Hitler that ‘You are Germany! When you act, the nation acts!’. However, Metropolis contains no such axis, and its masses are influenced by multiple figures, none of whom come close to Hitler’s power, including Freder, the foreman, and the real and false Marias. Instead, when the real-Maria is preaching to the crowd, Lang uses match cuts mainly between her and Freder, establishing her as his privileged object but not the workers, and when the false-Maria leads them she often stands within or emerges from the masses.

The Head, The Hands, The Heart

There is one further critique of Kracauer’s which also needs addressing. The claim that Metropolis’ industrial overlord Frederson is embodied as an authoritarian figure through his son Freder, who helps him achieve ‘intimate contact with the workers’, allowing for a false sense of connection and the ‘establishment of totalitarian authority’. In this argument, Freder’s final status as the ‘heart’ between Metropolis’ ‘head’ and ‘hands’ works to provide a false sense of mediation in line with Goebbels’ belief that it is “better and more gratifying to win the heart of a people”.

However, Kracauer’s theory relies on the structure of Metropolis’s final scene in which the workers march towards Frederson in a wedge formation, which in his belief ‘denotes that the industrialist acknowledges the heart for the purpose of manipulating it’. However, this ascribes the geometry an ideological impetus which it does not possess. As already discussed, Lang does not construct the abstract masses as an expression or directive of its workers’ wills, and their final triangular formation is more coherently explained as a continuation of Lang’s mechanical obsession. The triangle is another shape with which Lang fetishizes his world, as found in the pyramidal structures of children who surround Maria during the flood, the triangles flashing around the Babylon intertitle during the real Maria’s workers’ sermon, and the intertitles which transfer us from Metropolis’ underworld to its ‘Eternal Garden’. Even the city’s skyline consists of pyramid-like skyscrapers. Therefore, the ending is not an endorsement of mediation, nor a cinematic antecedent to Hitler’s self-mythologising in Triumph, but rather a simple continuation of Lang’s obsession with structure and mechanics.

Conclusion

There are clear similarities between Metropolis and Triumph of the Will’s use of scale and mass. Both films lean heavily into their decorative patterning and reduce individuals to mere components in an ornament of spectacle. However, this alone does not provide a tangible link between the two films, and the clear differences with which Lang and Riefenstahl frame, construct and utilise their masses point to profound differences between the two filmmakers and their works. This completely undermines the charge that Metropolis can legitimately be read as a form of proto-fascist filmmaking.

Bibliography

Barsam, R. M. (1975). Filmguide to Triumph of the will. Bloomington : Indiana University Press. http://archive.org/details/triumphofwill0000rich

Begam, R. (2021). From Automaton to Autonomy. In A Modernist Cinema. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780199379453.003.0005

Benjamin, W., & Jennings, M. W. (2010). The Work of Art in the Age of Its Technological Reproducibility [First Version]. Grey Room, 39, 11–38.

Eisner, L. H. (1973). The haunted screen: Expressionism in the German cinema and the influence of Max Reinhardt / by Lotte H. Eisner. Secker & Warburg.

Hales, B. (1992)”Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and Reactionary Modernism” New German Review 8.

Huyssen, A. (1981). The Vamp and the Machine: Technology and Sexuality in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. New German Critique, 24–25(24/25), 221–237. https://doi.org/10.2307/488052

Jonsson, S. (2013). Crowds and democracy: The idea and image of the masses from revolution to fascism / Stefan Jonsson.Columbia University Press.

Kracauer, S. (1966). From Caligari to Hitler: A psychological history of the German film / by Siegfried Kracauer. Princeton University Press.

Quaresima, L (2004) Introduction in Kracauer, S. (1966). From Caligari to Hitler: A psychological history of the German film / by Siegfried Kracauer. Princeton University Press.

Kracauer, S. (1995). The mass ornament: Weimer essays / Siegfried Kracauer / translated, edited, and with an introduction by Thomas Y. Levin. Harvard University Press.

Neale, S. (1979). Triumph of the Will: Notes on Documentary and Spectacle. Screen (London), 20(1), 63–86. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/20.1.63

Neale, S. (1983). Masculinity as Spectacle. Screen, 24(6), 2–17. https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/24.6.2

Rutsky, R. L. (1993). The Mediation of Technology and Gender: Metropolis, Nazism, Modernism. New German Critique, 60(60), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/488664

Salkeld, A. (1996). A portrait of Leni Riefenstahl / Audrey Salkeld. Jonathan Cape.

Schoenhals, M., & Sarsenov, K. (2013). Imagining Mass Dictatorships: The Individual and the Masses in Literature and Cinema / edited by Michael Schoenhals and Karin Sarsenov. Palgrave Macmillan.